The House

Click to Enlarge

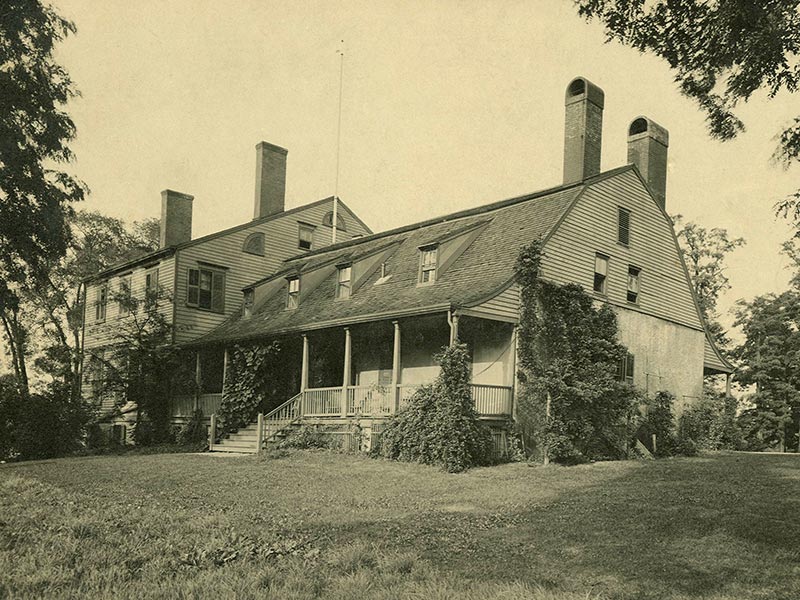

Mount Gulian has stood on a hill above the Hudson River since about 1730, almost 300 years. Occupied continuously by the Verplanck family until a fire destroyed it in 1931, the fieldstone house and Federal era addition were beacons of literacy, taste and comfort for generations. At the time of the fire, family members, household staff and neighbors rescued some furniture, paintings, and valuables from the home. The ruin, with just the stonework foundation and brick chimneys remaining, was then left to the mercy of the elements for thirty-five years.

In 1966, Bache Bleecker, a direct Verplanck descendant and his wife Connie, founded the Mount Gulian Society for the purpose of reconstructing the homestead and saving it as a museum and historic site for future generations.

The newly formed Mount Gulian Society immediately hired a restoration expert, Edward Litwin. He excavated the ruins of the old stone homestead during the summer of 1967. All that remained was a cellar choked with weeds and the rubble of old handmade bricks and cut native sandstone, and low remnants of stone walls, fireplaces and chimneys. The Federal addition, once an elegant two-story wooden structure was completely gone. To help him with the reconstruction, Mr. Litwin studied old photographs and consulted people who remembered Mount Gulian as it was, although the dwelling had been changed internally many times over its long life.

Click to Enlarge

The original house was built between 1730 and 1740 by Gulian Verplanck II, a merchant from New York City. It was a small stone structure capped with an A-roof, typical for colonial houses on the frontier at that time. That the house gradually grew in size came as no surprise to Litwin. From a stone in the cellarway with “1767” carved on it, he concluded that the house was probably enlarged around that time. The stone foundation indicated that the two porches, front and back, and the hallmark gambrel roof were probably added sometime after 1767, but before the Revolutionary War in 1775.

In 1804, Gulian II’s grandson, Congressman Daniel Crommelin Verplanck, built the Federal-era addition and with the assistance of his precocious 11 year old daughter, MaryAnna, laid out the decorative English style garden, the rage at that time. General Lafayette, on his famous return to America in 1824, stayed in a room in the addition and planted a rosebush in the garden. The Mount Gulian Society decided not to rebuild the addition. The house would be reconstructed to its 1783 state, when patriot General von Steuben used it as his headquarters and the Society of the Cincinnati, America’s first veterans’ fraternal organization, was founded.

Click to Enlarge

The restorers dug deep to reach Mount Gulian’s colonial days. Part of a large fireplace, complete with beehive oven for baking, was found in the northeast corner of the cellar, as were huge brick arches anchoring the first floor fireplaces from beneath. Once the ruins revealed all they could, construction began; new oak floor beams and pine floor planking, of the same dimensions as the originals (the planks are fascinatingly irregular) went into place along with first floor Dutch doors and window frames. A few 18th century glass panes, with wavy-appearing glass, were set into the new windows. Mr. Litwin and his sons strengthened and pointed up the remaining original stone walls and completely restored the fireplaces.

By autumn 1970, the roof was framed, sheathed and covered with colonial-looking cedar shake shingles. The following summer, both porches were reconstructed. Now the Dutch-style gambrel roof, curving bell-shaped to the porch columns, restored the house to its former grace. Land clearing the overgrown, neglected site revealed stately old trees, some of them unusual specimens long forgotten. In 1973, a local blacksmith fashioned hinges and other hardware for doors and shutters. Reconstruction was completed in 1975, one year ahead of schedule and America’s Bicentennial Celebration.

Click to Enlarge

Today, visitors are invited to enjoy the colonial-era reconstructed architectural features, built with an eye toward historic accuracy and craftsmanship. These include the roof, which slopes down and outward in a graceful bell-like curve to become the roof of both porches; the original cellar colonial kitchen and beehive oven; and the four capped chimneys. The Museum House today is weatherized and comfortable, open to the public for tours, special events and educational programming. It overlooks the scenic grounds and Hudson River as it has for nearly three centuries, featuring exterior Dutch-doors, a meeting/exhibit room, a museum room featuring 19th century pieces, and the southeast dining room. The museum offices are upstairs. Adjacent to the home is a restored circa 1730 Dutch-style barn, original to the Verplanck family, brought from a nearby property and rebuilt on site.