The Wappinger People

Survey archaeology at Mount Gulian indicates that the Mount Gulian site had a long history of seasonal occupation by the ancestors of the Wappinger Native Americans. Native Americans lived intermittently, in seasonal encampments on the property from around 8,000 BP (Before the Present). The camps were occupied until the "contact period" in the early 1600’s.

The Wappingers (Wappinnee, Wapinck, Wappinge) and related Native American communities lived along the eastern banks of the Mahikannituck (Hudson River), from modern Dutchess County NY, east into central Connecticut, and south into Westchester County. They spoke an eastern-Algonquian dialect of the Lenape-Munsee language. Culturally they are Lenape People (aka Delaware Indians) whose ancestral lands, known as Lenapehoking, stretched to the west across the lower Catskills and mid-Hudson region, south through New Jersey and central Long Island, to the Delaware and Chesapeake Bays. "Wappinger" means "easterner" in most Algonquian languages.

As the Ice Age glaciers receded, the First Americans lived in rock shelters and seasonal camps, such as at Mount Gulian. Gradually they lived in semi-permanent villages and developed a local form of agriculture, planting and harvesting crops such as sunflower seeds, tobacco, corn, types of squash and many bean species. But the largest part of their diet was always from the bounty found in nature, especially ground nuts, berries, leafy plants, fish and wild game.

Wappingers wore warm clothing made of deerskin and slept on bearskin blankets in the snowy winters. They sometimes covered their bodies in animal grease as insulation from the cold (and insects) and they wore moccasins in winter and deer skin leggings to stay protected from thorns and sticker bushes. The women watched over small gardens and fields, took care of the children, wove fine baskets and platters made of local grasses, tended to the animal hides, and handled much of the food gathering, preparation and food storage. Men hunted, went on seasonal fishing trips and trade expeditions to other Native communities and protected the community from enemies. By living close to the cycles of nature and watching the signs of seasonal change, Native People had balanced diets and were generally healthy and robust, as reported by many early European observers.

Spiritually, the people were aware of the powers and spirit-souls in all living things and considered all living beings as relatives. They believed in a Great Creator who loosely controlled the natural world and the cycles of life. Natural things such as the river waters, the land, mountains, the sky and all living things had sacred spirits which were acknowledged and respected. Many of the Wappinger and Lenape rituals, rites of passage, ceremonies and food hunts were directly tied to honoring and interacting with these spirits for the benefit of the entire community. Acknowledging the seasons and the bountiful production of nature, especially food-giving animals and plants, was central to their customs.

With more dependable agriculture, Native Americans such as the Wappingers created village settlements, sometimes surrounded by a wooden palisade or fence. Villages were not usually permanent, but used for a decade or so until moved, when the surrounding area was depleted of natural resources. The most important element in their village communities was the extended family, which was grouped into clan or kinship systems by lineage from an important elder or spirit (totem) animal. Each clan had their own ceremonies and traditions, and would sometimes branch out into temporary quarters outside the village for special gatherings. Women were often clan leaders in Lenape society. The importance of extended families and the clan system in Native life cannot be overstated.

Wappinger homes in the village were made of wooden framed saplings covered with bark and sometimes animal hides. Wigwams, where most families lived, were round in shape and warm and sturdy in winter. They had a roof hole to allow smoke from the central hearth fire to escape, covered by a hide in times of rain. Wigwams could also be temporary, used in hunting and gathering camps. Larger “longhouses” were rectangle in shape and could house 40-60 people. Some settlements would have over twenty wigwams surrounding a central longhouse and other large ceremonial buildings and workshop spaces for tool making, pottery making and hide processing. Settlements near fresh water and good garden spots could remain in one place for twenty years or so, until the people moved the town to a fresher location a few miles away.

In 1609, Henry Hudson encountered Lenape people in New York harbor and throughout the Hudson River Valley. These Native American cultures and their ancestors had lived in the area for thousand years. Hudson reported that these people were healthy looking, for the most part friendly, independent minded and numerous on both sides of the river. The Dutch settlers took control of and then inhabited traditional Lenape and Wappinger lands as part of the New Netherlands Colony from 1609-1664. During that time, Wappinger life turned very bitter as they gradually lost their traditional ways and lands. Many left their lands to move away from European settlements, migrating with other Native communities further north and west. Many died of the new diseases the settlers unknowingly brought from Europe. Some Natives gave up their ancient Indian culture and were converted to Christianity by missionaries. Others were killed in numerous brutal wars with the Dutch, or were captured and sold into harsh slavery in other parts of the New World including the Caribbean Islands, from where they never returned. By the end of Dutch rule in America, the Wappingers had become terribly weakened.

In 1666, the Dutch New Netherlands permanently became part of the British Empire. The Dutch settlers declared their loyalty to the British Crown, as did the Wappinger Indians, but the Wappinger people were being quickly pushed out of their lands by the colonists. The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) People had long been enemies of the Lenape, to whom they had previously honored and paid tribute. With British muskets, the Iroquois punished the Lenape and raided their towns, forcing them into near destruction. By the 1680’s, after years of war and turmoil, the Wappinger Indians began to make difficult decisions.

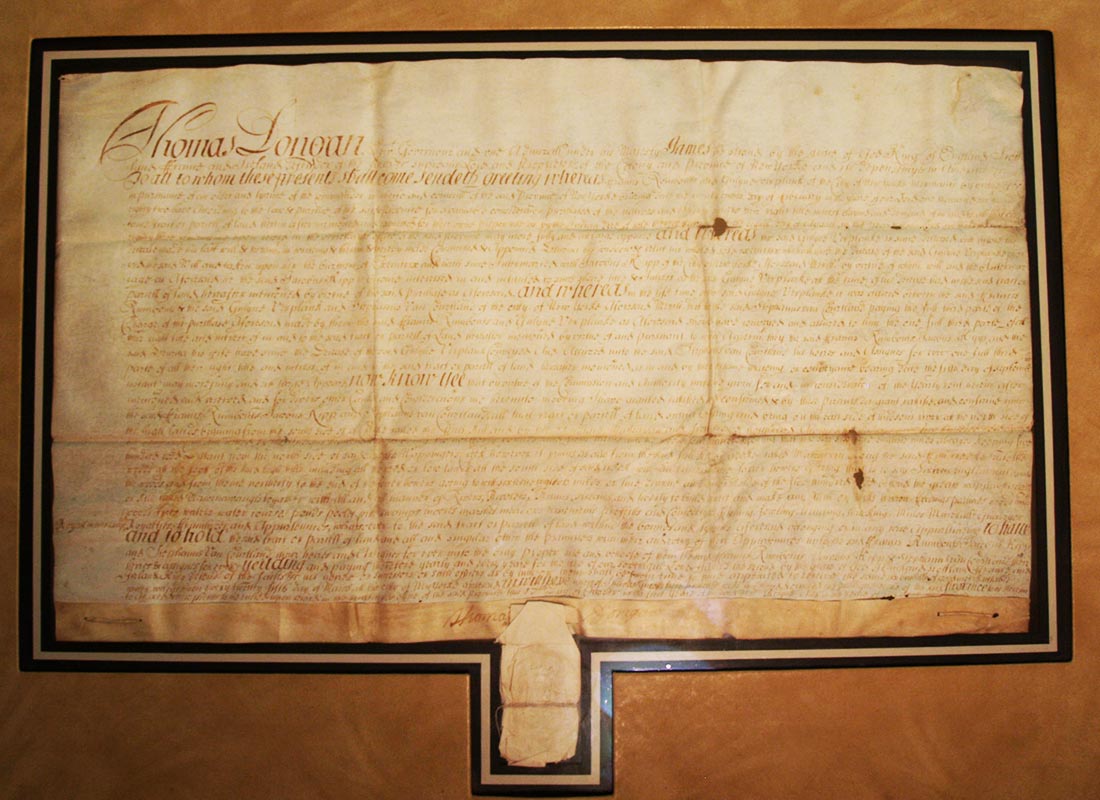

On August 8, 1683 an "Indian Deed of Sale" was written, selling 85,000 acres of Wappinger lands in present Dutchess County, NY, to Francis Rombout and Gulian Verplanck. Twenty-two Wappingers made their marks on the Deed (they could not write in English), which was recorded among the State papers at Albany, NY on August 14th, 1683. In return for 85,000 acres of land, the Wappingers received perhaps $1,200 worth of trade goods, including wampum, guns, gunpowder, cloth, shirts, rum, tobacco and beer. We do not know for certain if the Wappingers understood this “sale” meant that they had to leave their ancestral lands permanently. Did they understand that this Deed meant that they could no longer live on the land, that their claim to the land was now extinguished forever? Perhaps they believed that the Deed meant that they could still use the land to hunt, fish and grow gardens, sharing the land with the settlers, because no one can “own” land any more than anyone can own the air or sky. Perhaps they understood all too well that they were being forced off, and to get $1,200 worth of trade goods was better than nothing. Their thoughts on the Deed are not recorded. The Deed was reviewed by King James II's ministers and the “Rombout Royal Patent” was issued by the Crown on October 17, 1685, formally granting the 85,000 acres, one-seventh of Dutchess County to Gulian Verplanck and Mr. Rombout. This meant the Wappingers no longer could live on their ancestral lands and most began their migration out of the area. From the 1680’s until the Revolutionary War, the remaining Wappingers began slowly leaving this area, joining the Lenape, the Mohicans to the north, and even joining their former enemies, the Iroquois, who were all suffering from the upheavals of white settlement, disease and war. Many converted to the religion of the white settlers and permanently left their traditional ways.

Around 1730, Gulian Verplanck (the grandson) built a fieldstone house on the Rombout Patent property in Matteawan (now Beacon) and named it Mount Gulian, beginning a new era. During the Revolutionary War (1775-1783), the Wappingers and most Lenape declared their loyalty to George Washington’s new nation. Many Wappinger and Lenape warriors fought and died with the Americans, including Wappinger sachem and hero Daniel Nimham and his sons. By the end of the Revolutionary War in 1783, very few Wappingers lived on their former lands. In fact, some had already moved north to join the Mohicans in Stockbridge MA, or moved north into Canada. Others moved west into the Ohio Valley, and further west into Texas and finally Oklahoma and Wisconsin where they still reside.

Today, after many sad journeys, few people identify themselves as "Wappinger". Many married into White families and blended into modern America. Today, over 20,000 Americans and Canadians identify themselves as Lenape or Delaware. Most live in Wisconsin, Oklahoma and Ontario as Federally recognized U.S. tribes or Canadian First Nations. The people continue to maintain their dignity, heritage, language and their traditional ways. At Mount Gulian, we respect and honor the Wappinger People and seek to teach our visitors about their long history on this land, and their enduring ways.